You Can’t Force a Person to Learn Something

This article was featured in our weekly newsletter, the Liberator Online. To receive it in your inbox, sign up here.

Me: Can I force you to learn something?

The Young Statesman (then 12): No. You can not.

Me: So, if I sat you down and did chemistry lessons with you and threatened to….

YS

YS: Take something away?

Me: Yes. Take something away. If I threaten to take something away if you don’t do well on a chemistry test I give you will that make you learn it?

YS: I’ll learn it, I’ll spit it out, and then I’ll forget it.

Me: Isn’t that learning?

YS: No. That isn’t learning. That’s wasting time.

Me: What if I gave you an incentive to do well on a chemistry test. Will that make you learn it?

YS: If I don’t want to learn it, I won’t learn it. I’ll just memorize it, spit it back out at you, and forget it.

Me: What about subjects that are important?

YS: Important to whom?

Me: To many adults.

YS: Does that mean it’s important to me? If I don’t want to learn it, I will not learn it.

Me: Some people say if you don’t learn a thing when you’re young then that field will be closed to you when you’re older.

YS: Like what?

Me: We could say science. If you aren’t exposed to science when you’re young….

YS: You won’t be exposed to it again? You weren’t exposed to libertarian thought and Austrian economics when you were young and look at you. You’re running a page with over 25 thousand likes.

Me: What you’re saying is that I’m teaching people about liberty and Austrian economics and I wasn’t exposed to it as a child.

YS: Right. You were never exposed to that when you were little. Just because you weren’t exposed to it then doesn’t mean you won’t be great at it later.

Me: You’ve watched me teach myself, haven’t you?

YS: I have. I’ve watched you teach yourself a lot. I’ve watched you teach other people, too.

Me: You’ve watched me tutor. You’ve been in the room with me when I’ve tutored. What have you learned by watching students struggle with subjects they’ve been told are “important” but aren’t aren’t important to them?

YS: They want to make their teachers happy but the subjects aren’t important to them so they aren’t going to excel. Daisy was an artist. They were trying to cram all sorts of other stuff into her.

Me: What did that do to her?

YS: You had to re-school her.

Me: What do you think was the most important thing for her?

YS: Art. She was a wonderful artist. You let her focus on that.

Me: Someone had told her it was more important that she be a mediocre, miserable student than a fantastic artist. One would have to be blind to miss that she was an artist.

YS: She was told doing what she was good at wasn’t as important as what the teachers thought was important.

Me: And what did the teachers think was important?

YS: Everyone being the same was important. Following the curriculum was important. Art wasn’t important.

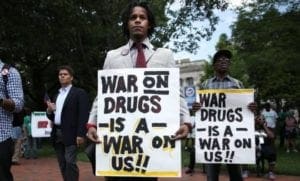

Me: It’s like a factory isn’t it? It makes one product.

YS: No variations. All the same thing.

Me: Does that work with people? Who does it reward?

YS: The state gets a nice new batch of uniform people.

Me: What happens to people like Daisy who are brilliant in something the school doesn’t value?

YS: Their talent gets squashed. I’ve noticed that you tutor the brilliant people. It’s the creative people who don’t do well in the school system.

Me: I would say that every child I’ve tutored had a burning passion that was being neglected or misdirected or devalued. I don’t think there’s one child I’ve worked with who wasn’t obviously being sold short. Can you imagine being a fantastic artist and having to sit in classes that bored you, that you weren’t interested in, that you actively hated and that you were failing every day of your life?

YS: I can not imagine how bad that would be. That would basically be the first eighteen years of your life thrown away.

Me: It would be worse than wasting it. It would be eighteen years of being told that you weren’t good enough. It would be a daily attack. We were talking about whether or not you can force a person to learn something.

YS: You can’t force a person to learn something.

Me: I was required to teach Daisy certain subjects. Do you think they stuck?

YS: No. She probably forgot them. It was probably a big waste of her time and your time.

Me: What do you think she remembered?

YS: That you let her do what she loved to do. That you understood what her talent was.

Me: I wish we had spent more time on art with her.

YS: She was a lot happier here than in school.

Me: Why is that?

YS: Because the government is charged with protecting our rights. That’s their job. I think that’s why people get confused.

Me: So how would you explain to someone what rights are and where they come from?

YS: I would explain that there are positive rights and negative rights. Negative rights are a duty to refrain from encroaching on the life, liberty, or property of another.

Me: Is that why they’re called negative rights?

YS: Yes. They’re negative because they’re saying what you can’t do. Negative rights are natural to every person. We have these rights just because we are people. We don’t have to enter into contract for these rights.

Me: So what another person has the right to expect you won’t do?

YS: Yes. So I have the right to expect that I won’t be killed, enslaved, or robbed. Life, liberty, and property. Positive rights are different. Positive rights say you have a duty to provide someone with something.

Me: How do you come about having a positive right?

YS: If a negative right was infringed upon, you have a positive right to restitution. You can also contract for positive rights

Me: Can you take away a peaceful person’s negative rights?

YS: No. If your negative rights haven’t been infringed upon and if you have no voluntary contract, then you have no positive right to a good service or anything like that.

Me: So what if I were to say that what you say about rights makes sense, but I still think rights come from the government?

YS: A legitimate government is just a group of people who have voluntarily gotten together to protect their rights. The rights that existed before the government came into being.

Me: Is there any great difference between a legitimate government and a voluntary mutual aid society that agrees to help one another protect their property?

YS: No. A legitimate government upholds people’s property rights and is voluntary. It doesn’t have a band of enforcers to force you the be part of their system. That violates the rights it claims to protect. If the government violates the rights it claims to defend it’s not legitimate. I should be able to say that I do not want their services. If you aren’t able to opt out, what are you? Do you have your liberty? Slaves aren’t able to opt out, are they? We just have a slightly bigger pen.

Me: Why is that?

YS: Because the government is charged with protecting our rights. That’s their job. I think that’s why people get confused.

Me: So how would you explain to someone what rights are and where they come from?

YS: I would explain that there are positive rights and negative rights. Negative rights are a duty to refrain from encroaching on the life, liberty, or property of another.

Me: Is that why they’re called negative rights?

YS: Yes. They’re negative because they’re saying what you can’t do. Negative rights are natural to every person. We have these rights just because we are people. We don’t have to enter into contract for these rights.

Me: So what another person has the right to expect you won’t do?

YS: Yes. So I have the right to expect that I won’t be killed, enslaved, or robbed. Life, liberty, and property. Positive rights are different. Positive rights say you have a duty to provide someone with something.

Me: How do you come about having a positive right?

YS: If a negative right was infringed upon, you have a positive right to restitution. You can also contract for positive rights

Me: Can you take away a peaceful person’s negative rights?

YS: No. If your negative rights haven’t been infringed upon and if you have no voluntary contract, then you have no positive right to a good service or anything like that.

Me: So what if I were to say that what you say about rights makes sense, but I still think rights come from the government?

YS: A legitimate government is just a group of people who have voluntarily gotten together to protect their rights. The rights that existed before the government came into being.

Me: Is there any great difference between a legitimate government and a voluntary mutual aid society that agrees to help one another protect their property?

YS: No. A legitimate government upholds people’s property rights and is voluntary. It doesn’t have a band of enforcers to force you the be part of their system. That violates the rights it claims to protect. If the government violates the rights it claims to defend it’s not legitimate. I should be able to say that I do not want their services. If you aren’t able to opt out, what are you? Do you have your liberty? Slaves aren’t able to opt out, are they? We just have a slightly bigger pen.